Medieval and early modern physicians understood epidemics through the lens of the theories developed by classical thinkers like Hippocrates and Galen. Health was defined by the balance of the body’s four humours, while disease was a product of their imbalance. Although many things could disrupt humoural balance, the most important determinant of disease was the environment.

Miasma theory held that ‘bad airs’ were a primary cause of disease—in individual bodies as in populations. Famous images of plague doctors wearing long, black face masks show the care taken to avoid infection from corrupt airs, while fires might be burned as a type of ‘disinfectant’, as happened at Magdalen in 1533/4.

Bad airs could arise from unsanitary conditions, decaying organic matter, or stagnant or putrid waters. It was also believed they could arise from the influence of the stars. Astrology provided an explanation for epidemics that fit well with prevailing medical ideas as well as with Christianity, since God used the stars and planets as His instruments on earth. The movements of the celestial bodies, in relation to the Zodiac, were said to govern epidemics. Physicians could therefore use horoscopes to draw conclusions about the onset, severity, and life of an epidemic.

Premodern physicians had theories about the ‘seeds’ of disease, but it was much easier to respond to macro-phenomena like poisonous airs than invisible particles. In the 17th century, however, with the development of powerful microscopes, more attention was paid to the role of minute particles in disease, paving the way for modern germ theory.

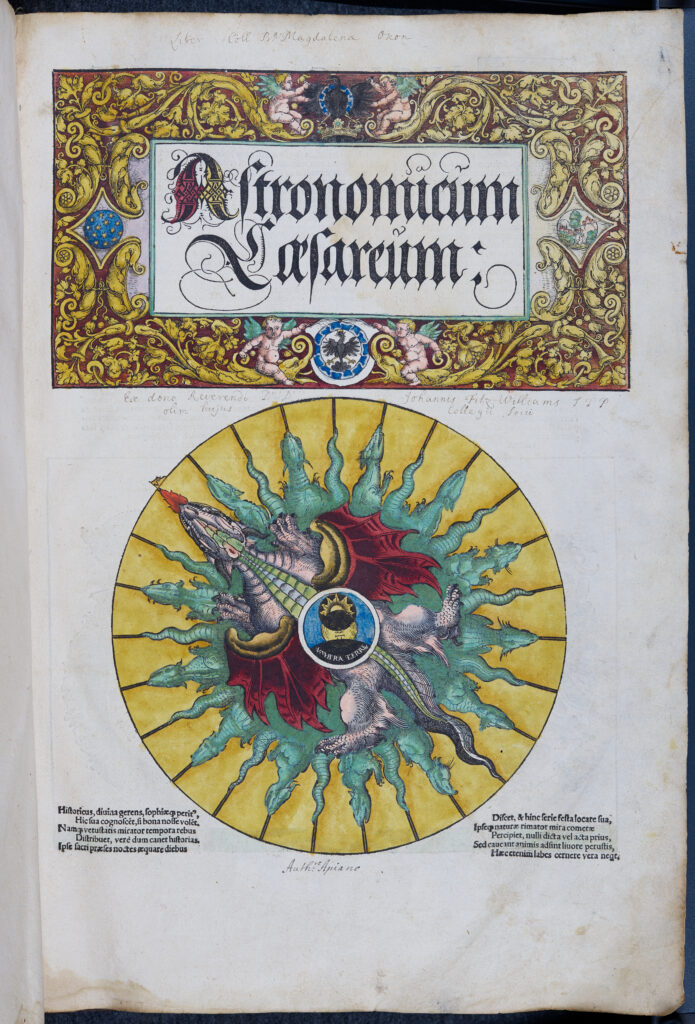

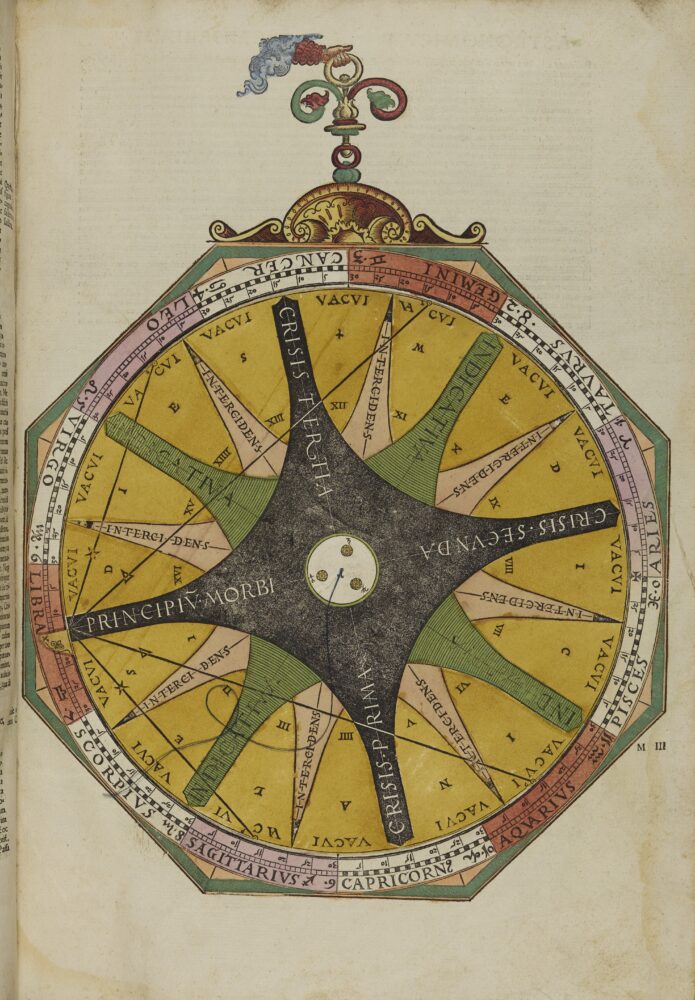

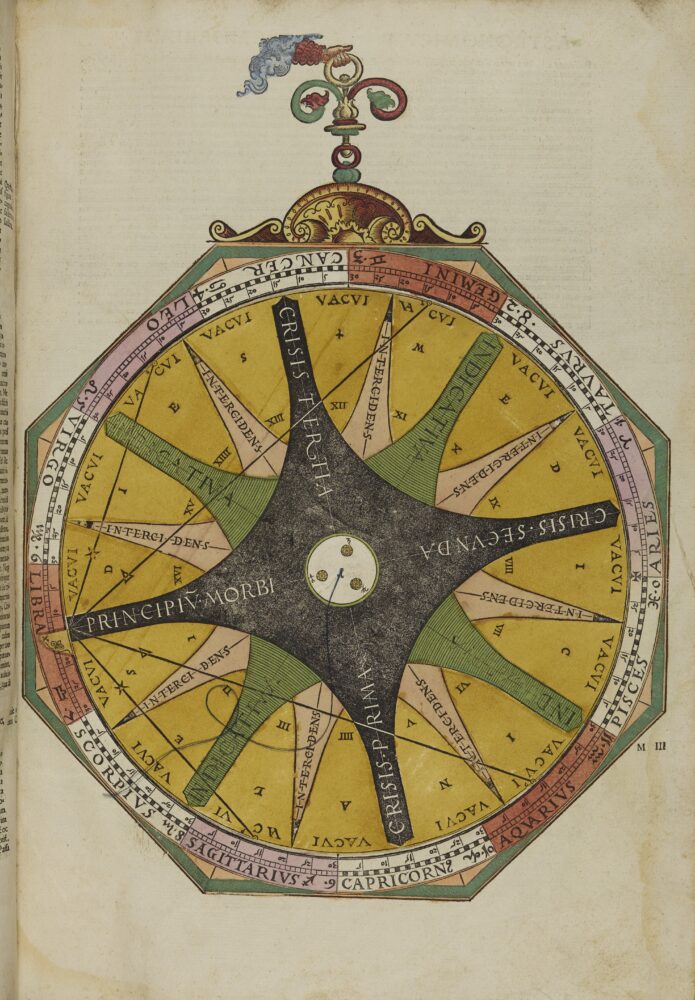

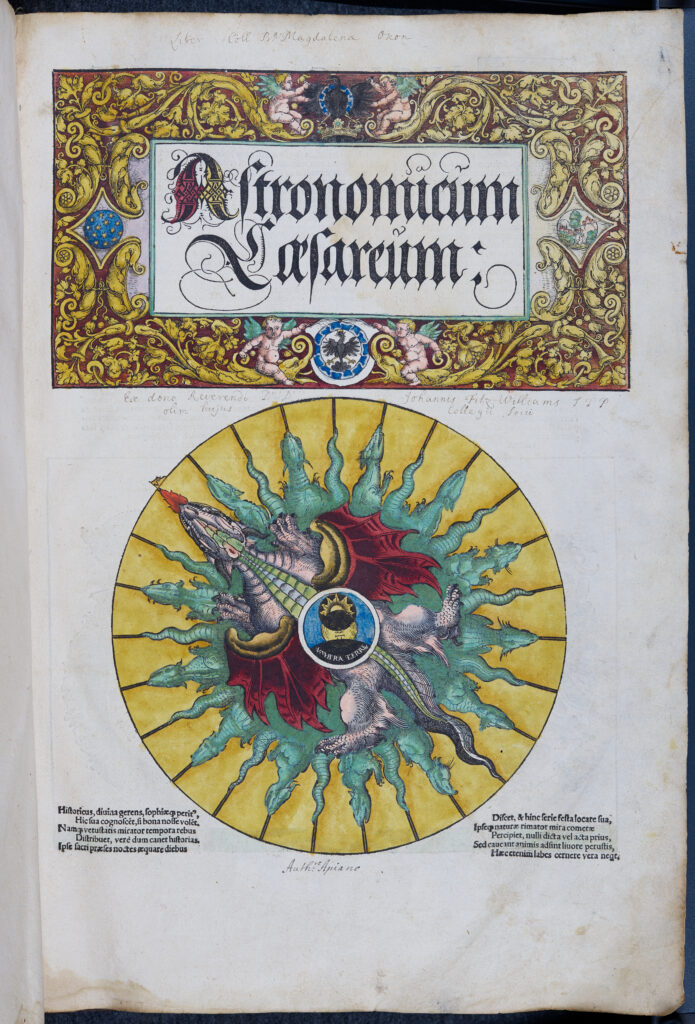

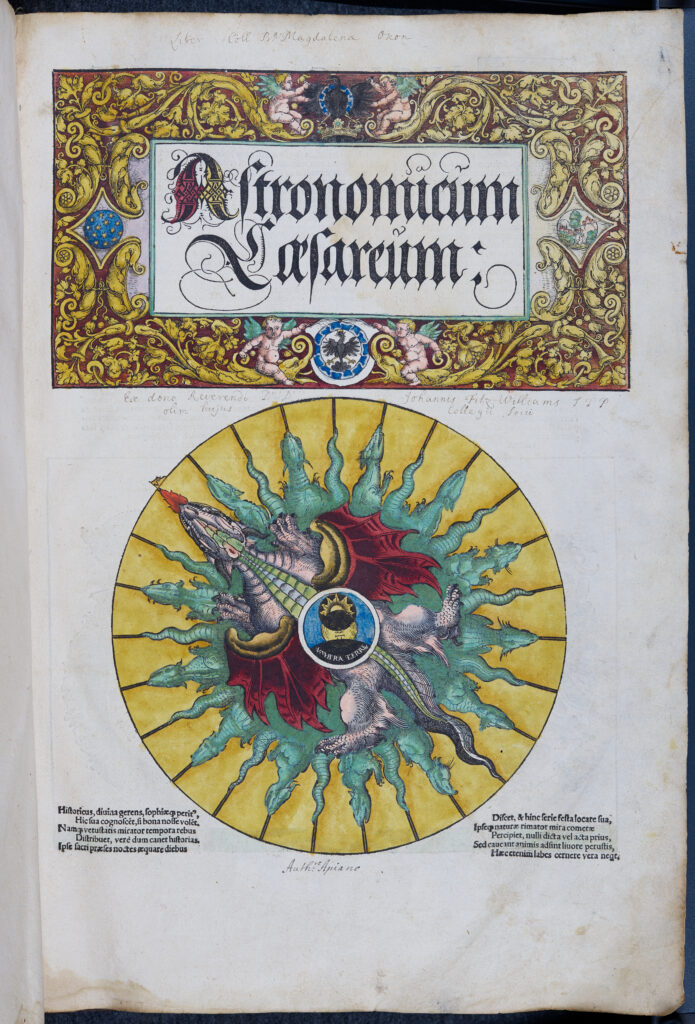

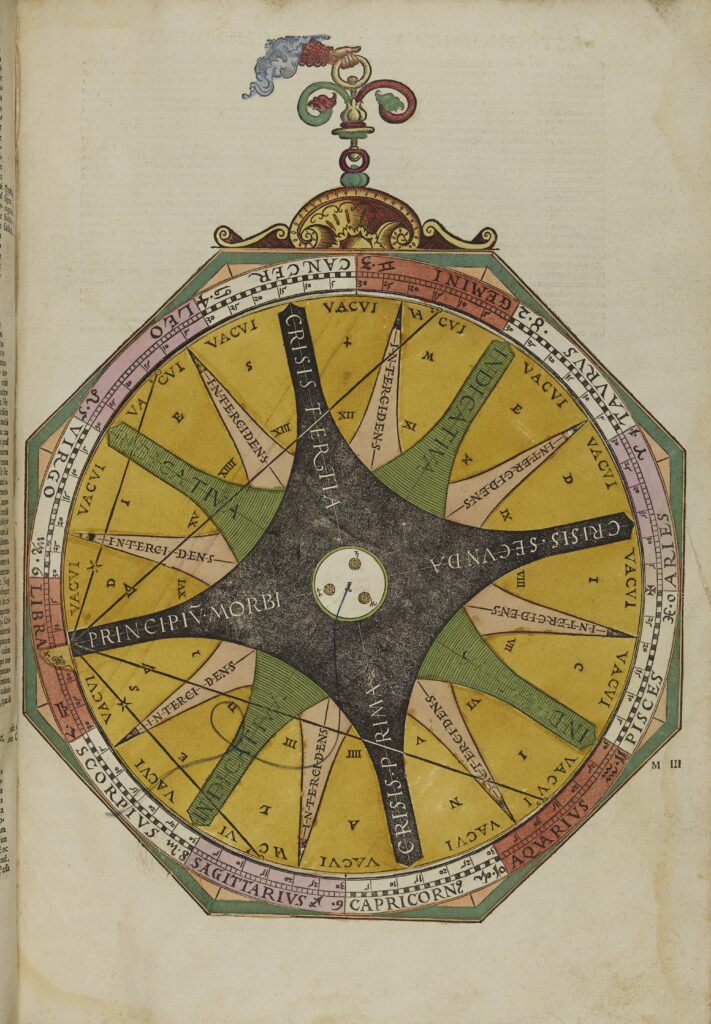

Astronomicum Caesareum

This exquisite book teaches readers how to locate the positions of the planets in the heavens, primarily for the purpose of casting horoscopes. The dragon volvelle depicted here—essentially a paper computer—was used to calculate lunar phases and make for more accurate predictions of eclipses.

Eclipses were thought to herald portentous events on earth, including epidemics.

This book was dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor; the ability to predict epidemics was a valuable tool for a state leader. The Library’s copy once belonged to John Fitzwilliam (d.1699), a student and later Fellow and Librarian of Magdalen.

Magdalen College Library, Arch.C.I.5.8

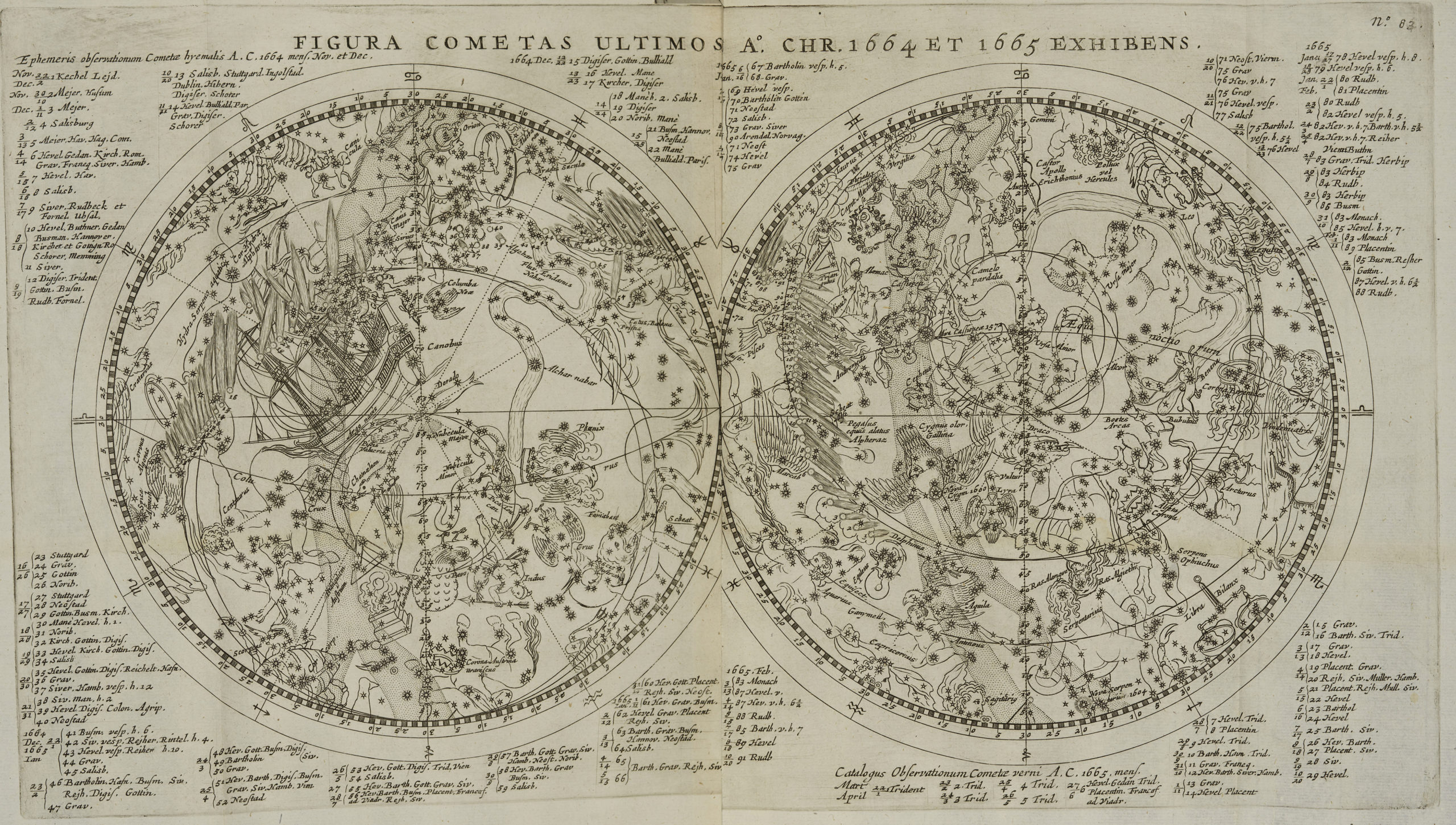

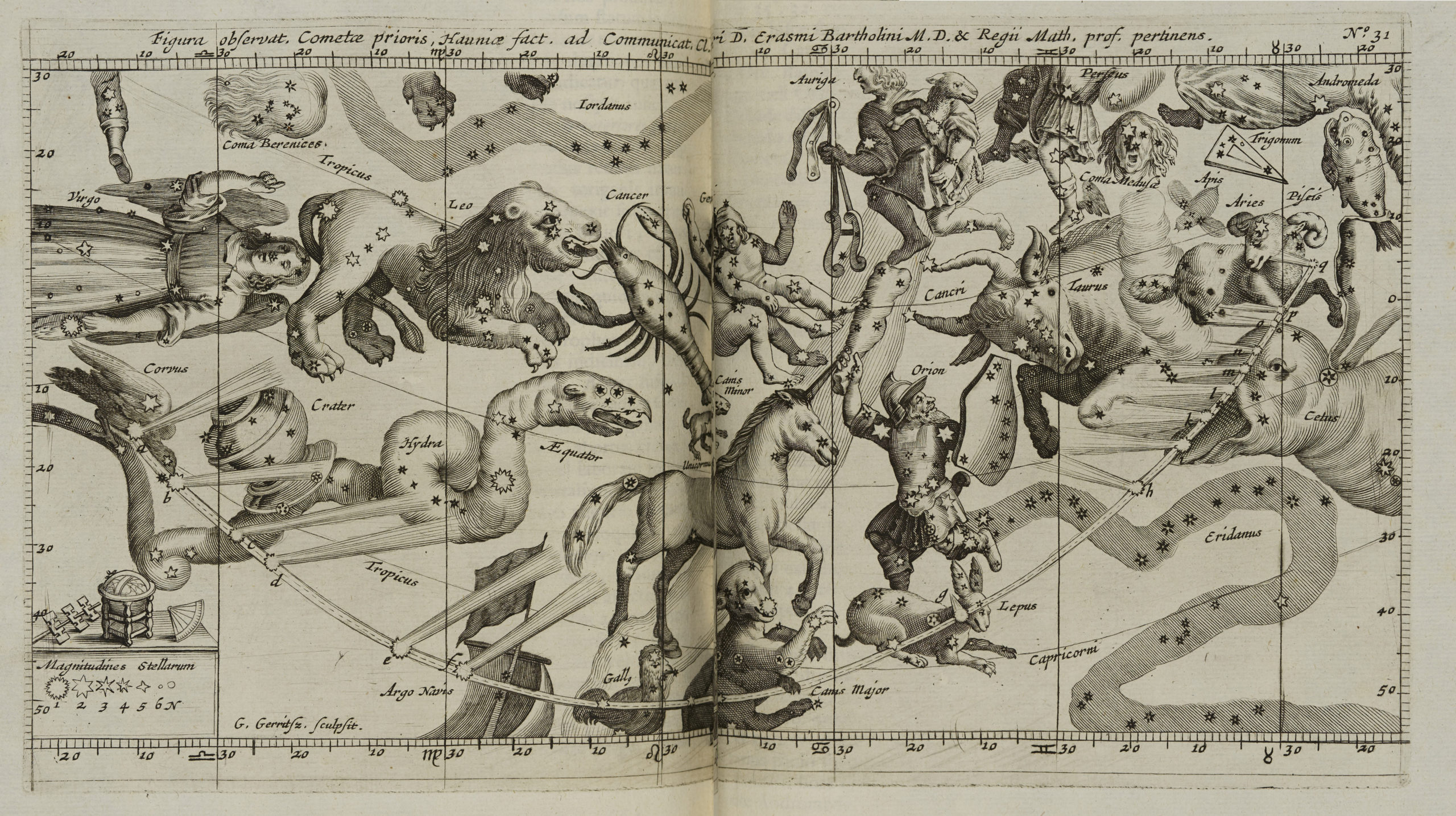

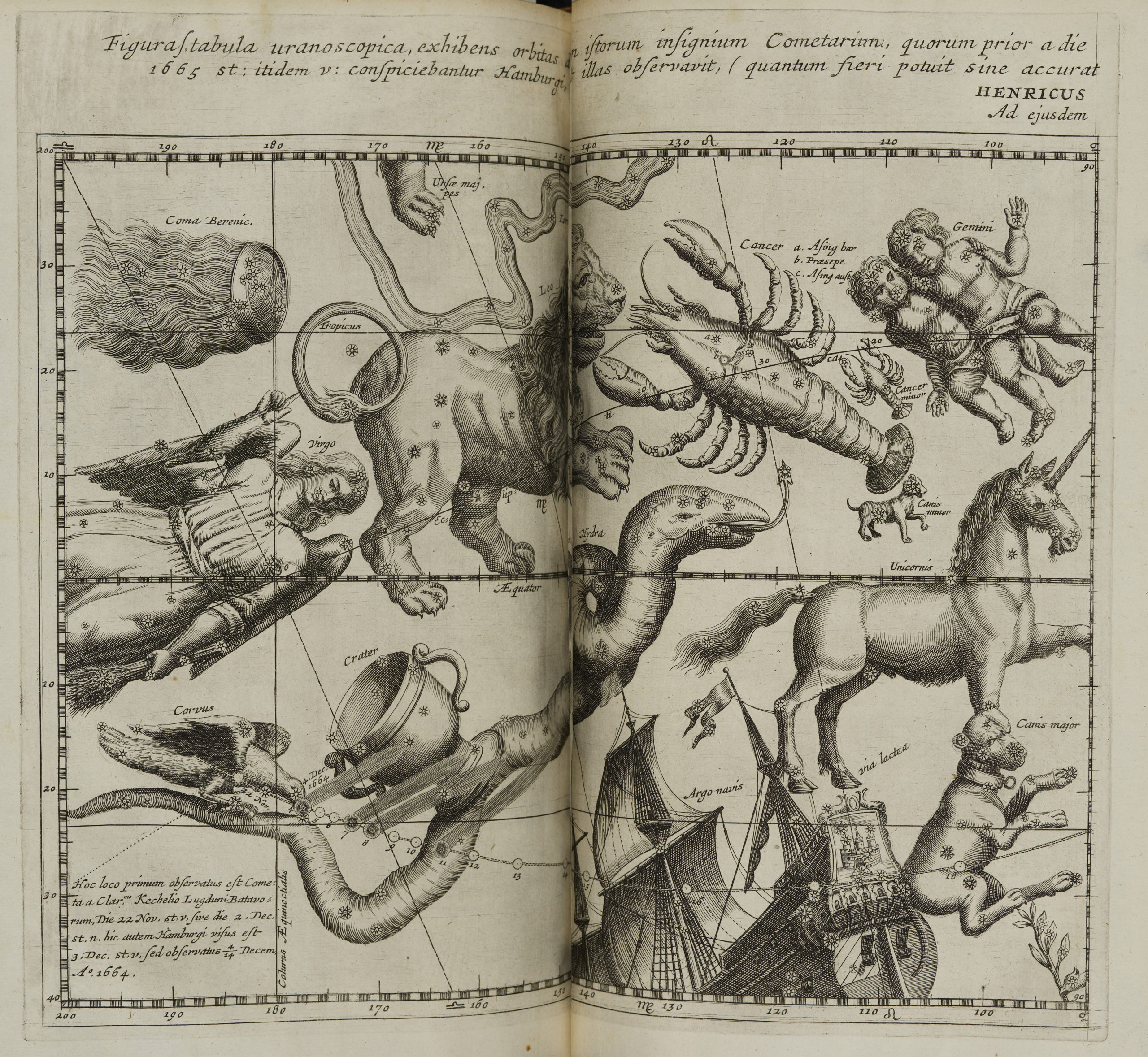

Theatrum cometicum

This lavishly illustrated book by the Polish theologian Stanislaw Lubieniecki (1623–75) describes the history of comets from Biblical times up to 1665.

Like eclipses, comets were thought to herald impending pestilence. Many thought that comets were not just signs but also causes of illness. Comets caused disease by issuing pestilent vapours, drying up the moisture in bodies and making them vulnerable to disease.

Magdalen College Library, q.10.9-10

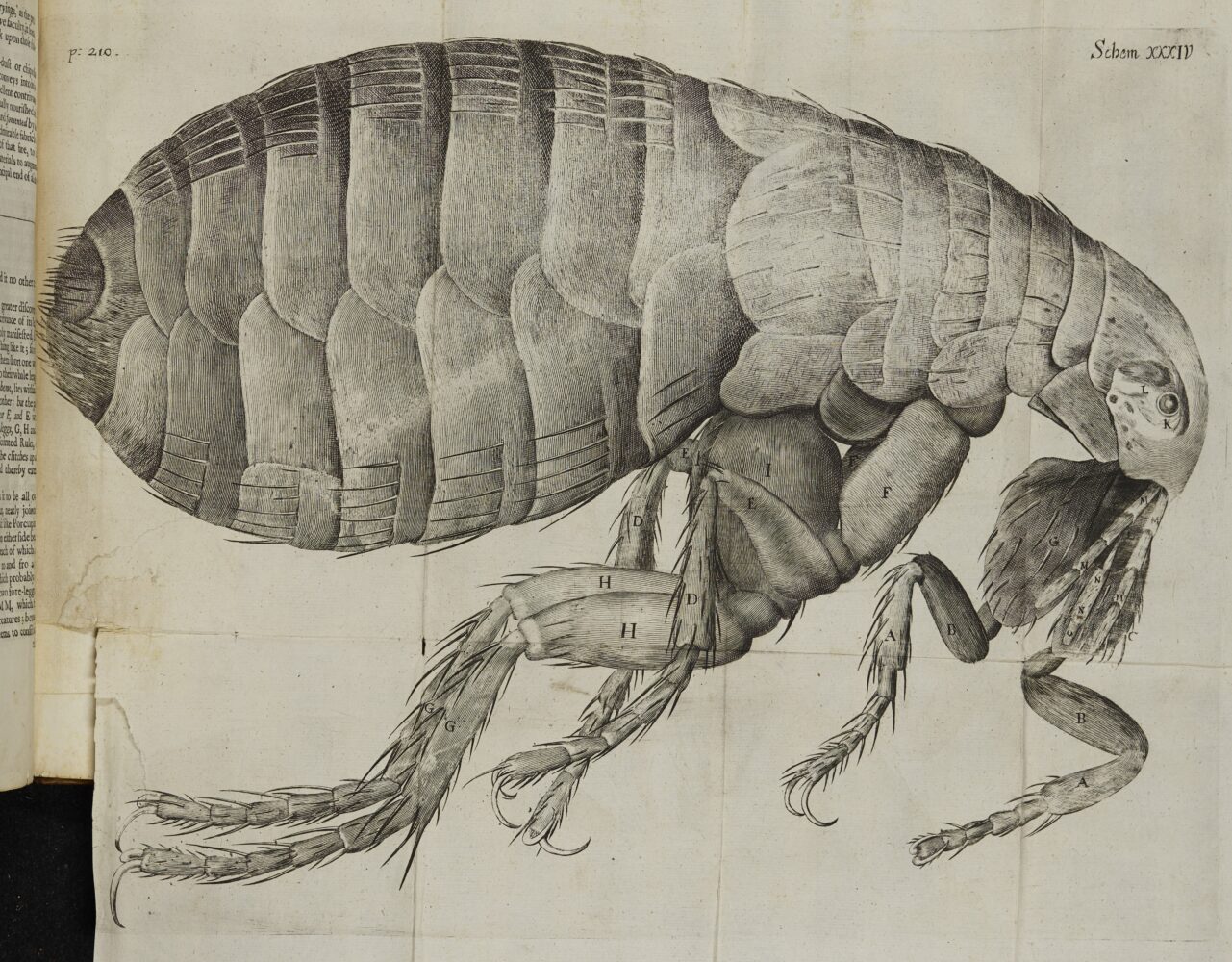

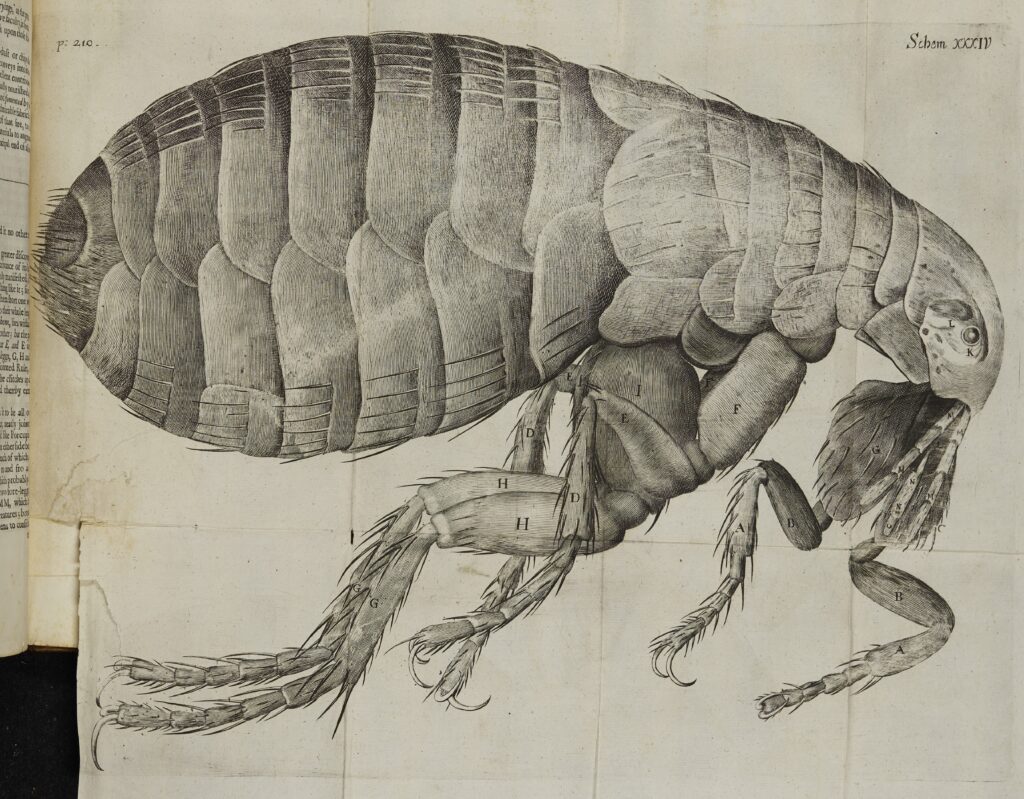

Micrographia

This book contains illustrations of the strange and wonderful things that the scientist Robert Hooke (1635–1703) saw under his microscope. Hooke was a member of a philosophical club at Oxford dedicated to experimental approaches to science and medicine that later became the Royal Society.

This intimidating image depicts a flea, which Hooke described as a ‘little soldier’. Although unknown at the time, fleas were responsible for the plague infection that was spreading throughout England in the very year this book was published, 1665.

The Library’s copy was bequeathed by Abraham Foreman (d.1667), Fellow and Librarian of Magdalen.

Magdalen College Library, q.12.17

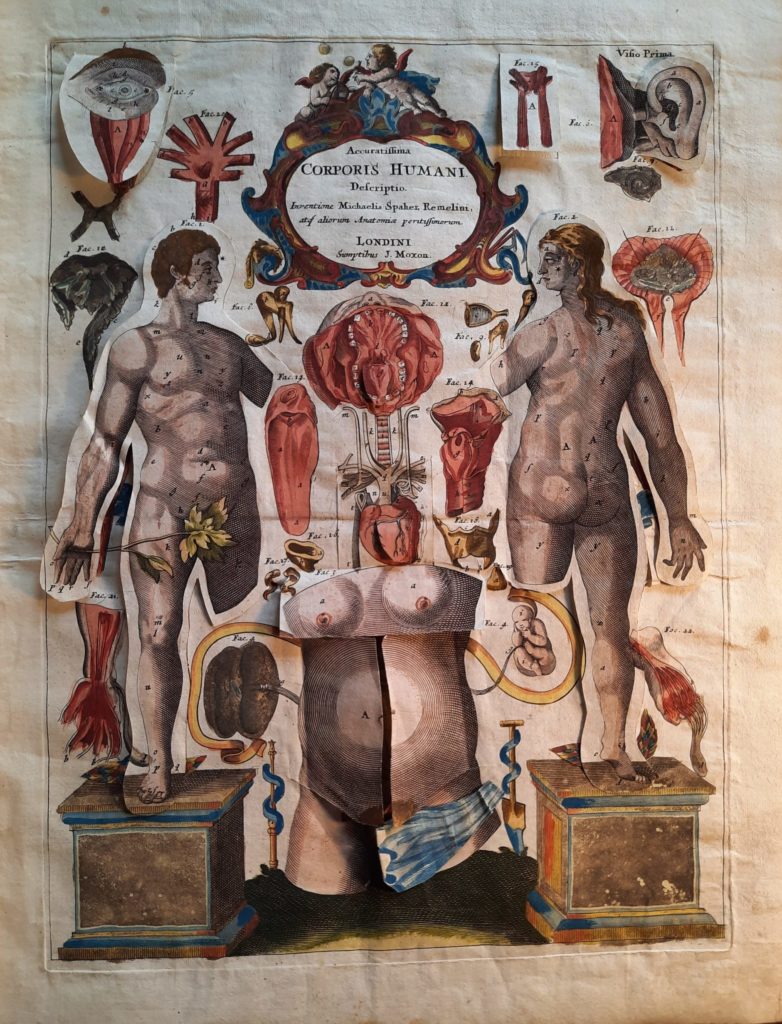

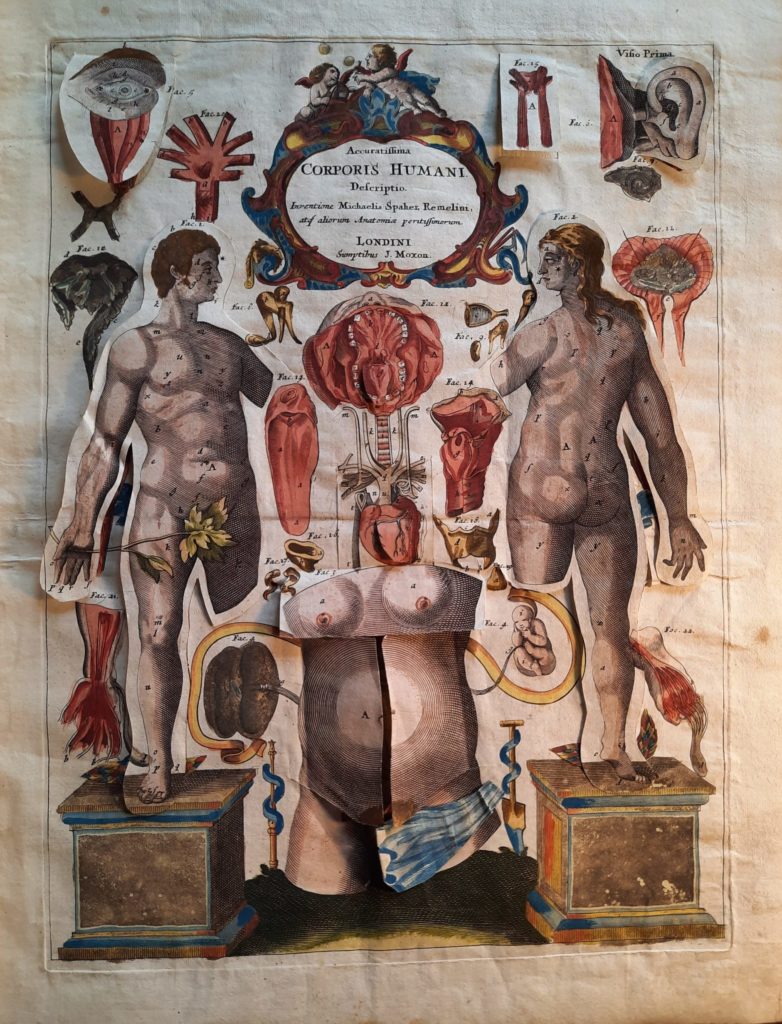

A Survey of the Microscosme

This remarkable anatomical book with moveable flaps demonstrates early modern interest in improving anatomical and medical knowledge amongst the reading public. When lifted, the flaps reveal layers of organs, vessels, and bones of the body.

Originally written by the German physician and anatomist Johann Remmelin (1583–1632), the book was translated into English by the surgeon John Ireton. Magdalen’s copy is vibrantly hand-coloured.

Magdalen College Library, Arch.C.II.5.5

Thomas Sydenham (1624–89)

Thomas Sydenham was a pioneer in epidemiological research in the 17th century. He began his university studies at Magdalen in 1642 and later ran a successful medical practice in London. Sydenham drew criticism from colleagues for removing his family to the country during the 1665 Great Plague, but he soon returned to help fight the pestilence.

Sydenham argued that febrile diseases like scarlet fever, pleurisy, and rheumatic fever were caused by problems in the body, while plague, smallpox, and dysentery were produced by climatic conditions. When it came to the latter, he believed effluvia emerged from the bowels of the earth in different forms year on year, contaminating the air and predisposing bodies towards particular diseases. Sydenham has been called ‘the English Hippocrates’ because of his emphasis on clinical observation over theory.

Magdalen College Library, q.4.21